Andrew Bujalski (a noted proponent of the mumblecore movement) has always had a preoccupation with language and its many forms, spoken and unspoken. His films tend towards barbed passive-aggressive commentary between idiosyncratic, socially dysfunctional characters that verbalize defensive tics while keeping subdued and unspoken the thoughts and feelings that could free them from a partially self-imposed prison.

As such, Computer Chess, a quirky departure from style and form, is, in a way, a logical progression of his work, having more of an abstract disposition and awareness of aesthetic and style as a secondary mode of telling a story that's more than the elements presented.

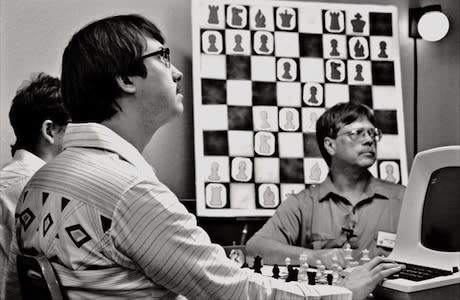

On the surface, this dry, oddly humanist experimental comedy is about an early '80s computer chess competition, wherein various programmers bring their oversized hardware to a drab hotel where their chess programs will compete against others. That these social rejects each demonstrate socially contrary behaviour while sitting adjacent to computers spitting out chess moves is an image and metaphor lost on no one.

As the tournament progresses, the computers demonstrate illogical behaviour, sacrificing queens early in the game or making moves their programmers didn't anticipate based on their language inputted. Though inexplicable within their lexicon of computational precision and logic, these hiccups mirror the fragmented and oft-disjointed stabs at communication between their human counterparts, who struggle to explain their rationale on the rare occasion they reach out.

Eventually, Bujalski abandons, or modifies, his initial stark realism. The 4:3 ratio and consumer-grade black & white video initially help date the film beyond the gimmickry of oversized computers, side-parted hair and leisure suits. However, it eventually gives way to more experimental first-person perspectives and colour and disorienting inserts just as the plot introduces a group of hippies led by an African healer and an abundance of fluffy cats to the framework.

Discussions about computer sentience arise, just as speculation about future practical uses of computer technology do, all relying on the framework of interpersonal relationships. At one point, a young, sleep-deprived programmer questions whether computers might try harder when playing against humans rather than other computers. A friend responds by deconstructing the distinction between reality and fantasy, or sanity and insanity, comparing the human ability to reason to a computer's ability to sustain a functioning program — everything, whether breathing or artificial, is boiled down to its singular parts.

This scientific assessment of the human experience and projection of reality is juxtaposed with the more romanticized and emotional assertions of a hippie couple trying to seduce the young programmer. They perceive a 64-square chessboard as a rigid and limiting environment, while he sees it as a boundless world of possibilities, tossing out a finite number to give them an indication. In essence, everyone is trying to connect with each other to win, get what they want or simply share the experience of life briefly, but the many questions and signifiers breaking down each individual make it a near-impossibility.

These latter discussions and Bujalski's conscious shift in structure and aesthetic suggest an expanded perception of black & white reality to something more comprehensive. In setup and questions posed, he examines, and raises discussion about, the nature of communication and connection in a way that almost contradicts itself, making fun of our tendency to overanalyze and project while doing just that.

His undoing, beyond the bigger in-joke of feeling superior to his subject, presenting it all as arbitrary without saying so or convincingly believing it, is sheer pretentiousness. The oddball vision and deliberately oblique exploitation of a medium that tends towards rigidity in a populist framework are commendable, but there's a smug sense of self-satisfaction and evasion in the presentation of past technology to a modern landscape. It's as though Bujalski is hoping to feign substance through nostalgia and mirroring, placing opposites together and throwing in a potpourri of loosely related elements without explanation to lead an audience, desperate to be included, to assume greater intentions and intellectual acuity on his part.

It's vaguely alienating, though the eventual, and inevitable, questioning of a computerized mindset about the nature of existence is at least a titillating melding of our relationship with spirituality and tenuous hold over technological advancement.

(Films We Like)As such, Computer Chess, a quirky departure from style and form, is, in a way, a logical progression of his work, having more of an abstract disposition and awareness of aesthetic and style as a secondary mode of telling a story that's more than the elements presented.

On the surface, this dry, oddly humanist experimental comedy is about an early '80s computer chess competition, wherein various programmers bring their oversized hardware to a drab hotel where their chess programs will compete against others. That these social rejects each demonstrate socially contrary behaviour while sitting adjacent to computers spitting out chess moves is an image and metaphor lost on no one.

As the tournament progresses, the computers demonstrate illogical behaviour, sacrificing queens early in the game or making moves their programmers didn't anticipate based on their language inputted. Though inexplicable within their lexicon of computational precision and logic, these hiccups mirror the fragmented and oft-disjointed stabs at communication between their human counterparts, who struggle to explain their rationale on the rare occasion they reach out.

Eventually, Bujalski abandons, or modifies, his initial stark realism. The 4:3 ratio and consumer-grade black & white video initially help date the film beyond the gimmickry of oversized computers, side-parted hair and leisure suits. However, it eventually gives way to more experimental first-person perspectives and colour and disorienting inserts just as the plot introduces a group of hippies led by an African healer and an abundance of fluffy cats to the framework.

Discussions about computer sentience arise, just as speculation about future practical uses of computer technology do, all relying on the framework of interpersonal relationships. At one point, a young, sleep-deprived programmer questions whether computers might try harder when playing against humans rather than other computers. A friend responds by deconstructing the distinction between reality and fantasy, or sanity and insanity, comparing the human ability to reason to a computer's ability to sustain a functioning program — everything, whether breathing or artificial, is boiled down to its singular parts.

This scientific assessment of the human experience and projection of reality is juxtaposed with the more romanticized and emotional assertions of a hippie couple trying to seduce the young programmer. They perceive a 64-square chessboard as a rigid and limiting environment, while he sees it as a boundless world of possibilities, tossing out a finite number to give them an indication. In essence, everyone is trying to connect with each other to win, get what they want or simply share the experience of life briefly, but the many questions and signifiers breaking down each individual make it a near-impossibility.

These latter discussions and Bujalski's conscious shift in structure and aesthetic suggest an expanded perception of black & white reality to something more comprehensive. In setup and questions posed, he examines, and raises discussion about, the nature of communication and connection in a way that almost contradicts itself, making fun of our tendency to overanalyze and project while doing just that.

His undoing, beyond the bigger in-joke of feeling superior to his subject, presenting it all as arbitrary without saying so or convincingly believing it, is sheer pretentiousness. The oddball vision and deliberately oblique exploitation of a medium that tends towards rigidity in a populist framework are commendable, but there's a smug sense of self-satisfaction and evasion in the presentation of past technology to a modern landscape. It's as though Bujalski is hoping to feign substance through nostalgia and mirroring, placing opposites together and throwing in a potpourri of loosely related elements without explanation to lead an audience, desperate to be included, to assume greater intentions and intellectual acuity on his part.

It's vaguely alienating, though the eventual, and inevitable, questioning of a computerized mindset about the nature of existence is at least a titillating melding of our relationship with spirituality and tenuous hold over technological advancement.