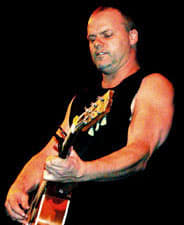

Canadian rock and roll was built by uncompromising personalities, but there hasn't been one in a long time like Fred Eaglesmith. The Southern Ontario-based singer/songwriter began splitting his time between music and farming in the early 1980s, but since making a full-time commitment to touring about ten years ago, and subsequently turning his songs in a markedly darker direction, Eaglesmith has inspired a legion of devoted followers from all over the world, while being roundly dismissed by the Canadian music industry. It's been a long time since he's cared about the latter.

"The thing about Canada is, we haven't done a big tour here in about a year-and-a-half, and I forgot that it's the only place in the world that doesn't return our phone calls," he says. "I don't think I'll ever figure out how things work here. Every time I feel I'm getting to the core, it starts feeling really dark and sinister. I've never been on CBC television or The Mike Bullard Show, and my only explanation is that Canada likes to play it safe. In one sense, I'm really glad about that. I can't bitch because I've gotten to do everything I've ever wanted without having to suck up to anybody."

His latest album, Fallen Stars and Broken Hearts, is another moving and humorous exploration of the complex characters that dominate the Canadian landscape outside of its urban centres. These are the people Eaglesmith grew up with, and they continue to make up the bulk of his audience. He celebrates this connection with frequent small-town gigs and the annual Fred Fest, which provides an opportunity for his scattered fan base to congregate and be exposed to other iconoclastic Canadian talent. It's also the most obvious symbol of Eaglesmith's large cottage industry, something he humbly admits every fan has a stake in.

"I can honestly say that I would sit down and have dinner with 95 percent of the people who come to my shows," he says. "I'm not a star and I'm not a radio personality, so this is how I have to do things. The way that guys like Hank [Williams] and Bill [Monroe] lived back in the 30s and 40s was a formula I could follow, and it has paid off in large dividends. But it's not something you get wealthy or famous by doing. You get wealthier as you go, but it's a slow, hard build."

"The thing about Canada is, we haven't done a big tour here in about a year-and-a-half, and I forgot that it's the only place in the world that doesn't return our phone calls," he says. "I don't think I'll ever figure out how things work here. Every time I feel I'm getting to the core, it starts feeling really dark and sinister. I've never been on CBC television or The Mike Bullard Show, and my only explanation is that Canada likes to play it safe. In one sense, I'm really glad about that. I can't bitch because I've gotten to do everything I've ever wanted without having to suck up to anybody."

His latest album, Fallen Stars and Broken Hearts, is another moving and humorous exploration of the complex characters that dominate the Canadian landscape outside of its urban centres. These are the people Eaglesmith grew up with, and they continue to make up the bulk of his audience. He celebrates this connection with frequent small-town gigs and the annual Fred Fest, which provides an opportunity for his scattered fan base to congregate and be exposed to other iconoclastic Canadian talent. It's also the most obvious symbol of Eaglesmith's large cottage industry, something he humbly admits every fan has a stake in.

"I can honestly say that I would sit down and have dinner with 95 percent of the people who come to my shows," he says. "I'm not a star and I'm not a radio personality, so this is how I have to do things. The way that guys like Hank [Williams] and Bill [Monroe] lived back in the 30s and 40s was a formula I could follow, and it has paid off in large dividends. But it's not something you get wealthy or famous by doing. You get wealthier as you go, but it's a slow, hard build."