In delivering one of the most striking hip-hop major label debuts in recent memory, Kendrick Lamar has not only put himself at the forefront of the West coast revival, but in position to be a highly influential player in the music's future. Lamar's inimitable artistry and self-assurance have been on display for a while now, but good kid, m.A.A.d. city is the uncompromising documentation of that treacherous journey of self-discovery. A heavily introspective tour de force, Lamar has created a stubbornly parochial soundtrack to his life in Compton, CA, set to a downbeat melancholy soundscape that incorporates the likes of Pharrell, Just Blaze and Dr. Dre, who are relegated to background walk-on roles. As the spectre of violence, death and paranoia hovers ubiquitously, we bear witness to a narrative detailing Lamar's transformation from a boisterous, impressionable, girl-craving teenager to more spiritual, hard-fought adulthood, irrevocably shaped by the neighbourhood and familial bonds of his precarious environment. What makes the album stand out from a rote coming-of-age story is the intricate attention to detail. Lamar's descriptive skills are so vivid that he immerses you in the topography of his world, his street corners and, ultimately, his state of mind. Lamar's descriptive skills on entries like "The Art of Peer Pressure" are so vivid, he immerses you in the topography of his world, his street corners and, ultimately, his state of mind. Even when it initially appears he may be bowing to convention, he isn't. "Poetic Justice," featuring Lamar and Drake in seduction mode over Janet Jackson's "Any Time, Any Place," could have gone the regular booty call route, but doesn't. This is underlined by the harrowing confrontation Lamar encounters after the song abruptly ends. Similarly, the album's T-Minus-produced lead single, "Swimming Pools (Drank)," addresses inner moral conflict, uncomfortable peer pressure and alcoholism when it could easily have been a mindless celebration of hedonism. Skits, so often the bane of hip-hop, serve as gritty mono audio aids to Lamar's storytelling, stitched together with interference-laden voicemails and rewound cassette tapes. And in era when style can often trump substance, Lamar takes this to the logical extreme, liberally playing with pronunciation, voice inflection and delivery, to the point where he inhabits different personas, mirroring the tumultuous emotional range and personal transformation on display. It also speaks to Lamar's latent urge to speak for those in his community who may not have been as fortunate. On 12-minute standout "Sing About Me, I'm Dying of Thirst," he rhymes from the perspectives of a deceased friend and a woman distressed by her sister's tragic life as a prostitute, portrayed in a previous Lamar song. Lamar then rhymes as himself, responding to the people in the first two verses. At one point in this verse, a weary and sober Lamar, cognizant of communal responsibility rather than self-exaltation, rhetorically asks, "Now am I worth it? Did I put enough work in?" From this vantage point, the answer is an unequivocal yes.

(Interscope)Kendrick Lamar

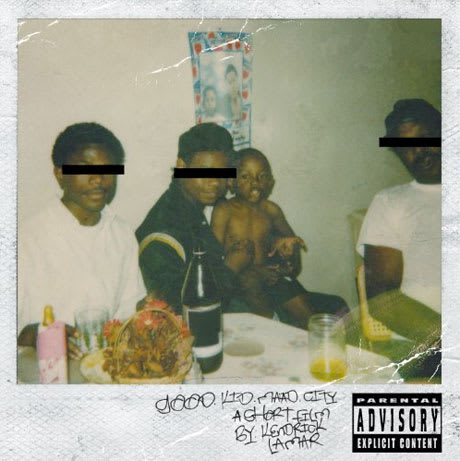

good kid, m.A.A.d. city

BY Del F. CowiePublished Oct 24, 2012

More Kendrick Lamar

- Drake Can’t Even Watch the Oscars Without Getting Made Fun Of

- Noel Gallagher Dismisses Kendrick Lamar's Super Bowl Performance as "Absolute Nonsense"

- Father John Misty Complains That He Has Once Again Been Upstaged by Kendrick Lamar