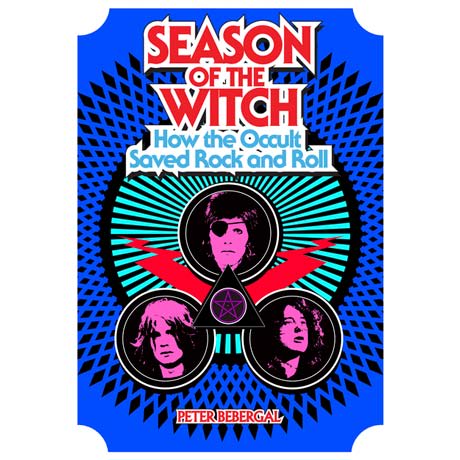

Peter Bebergal has succeeded in publishing an unfussy but thoroughly documented piece of prose on pop culture. With Season of the Witch, the author of Too Much to Dream: A Psychedelic American Boyhood establishes the occult as a phenomenon above and beyond its debatable status of mere fad in the history of contemporary music.

Without dwelling too much upon personal reminiscence, Bebergal sets the tone subjectively by bringing up memories of the youngster he once was, mesmerized by his older brother's rock album covers. His insistence on the multi-sensory experience resulting from his initial dabbling in rock'n'roll sparks ideas as to how he picked up on the subject matter of his most recent book. As a result, his descriptions of performances by Arthur Brown and his analysis of Brian Jones' interest in Moroccan Joujouka music bring to mind famed occultist Aleister Crowley's own definition of magic [magick]: "the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will."

Despite Bebergal's academic background as an Harvard Divinity School graduate, Season of the Witch comes off as a travel companion for the reader interested in whatever falls under the author's elastic definition of the word "occult."

While the outline of some stories included in the book might be familiar to many of Bebergal's audience, Season of the Witch goes way beyond rock'n'roll by touching upon musique concrete, hip hop, classical composers, electronic, ambient, free jazz, West African tribal music, stoner rock and death metal. Although some critics have expressed mixed feelings about Bebergal's regular back and forth between figures and eras, the subject matter's latitude makes it hard not to do so.

Consequently, the author's investigation of the influence of well-known occult figures (Gurdjieff, Crowley, LaVey, Osman Spare, Blavatsky, Mahesh Yogi, etc.) on music suggests the idea that there is a meeting of minds. In Season of the Witch, the external world, as seen through "occult lenses," becomes an art in itself — be it Charles Manson's mind control, Jaz Coleman's lyrics, George Harrison's immersion into Western philosophy, H.R. Giger's artwork for Brain Salad Surgery or Genesis P-Orridge's performances with COUM.

However, Season of the Witch's strongest moments are, without a doubt, Bebergal's analysis of the origins of the blues and his debunking of Robert Johnson's alleged pact with the Devil. As part of his investigation, Bebergal delves into conspiracy theories, Dungeons & Dragons, Greek mythology, LaVayan Satanism and neo-paganism. Under his eyes, the whole world becomes kaleidoscope and collides against a certain triumph of order and sanity in the age of fragmentation.

Strangely enough, Bebergal's authoritative account of how the supernatural shaped modern music leaves black metal out of the picture. The last chapters, which mention stoner rockers such as Sleep and OM, as well as Swedish arsonists-cum-deathmetalists (the latter of whom were essentially influenced by their Norwegian black metal counterparts), could — in the opinion of this critic — have used some tales about the Helvete shop and members of the "black circle."

In the end, the book does raise the question proposed by its title: Did the occult really save rock'n'roll? Probably not, but it did cause change to occur in conformity with some of its protagonists' will.

(Tarcher/Penguin)Without dwelling too much upon personal reminiscence, Bebergal sets the tone subjectively by bringing up memories of the youngster he once was, mesmerized by his older brother's rock album covers. His insistence on the multi-sensory experience resulting from his initial dabbling in rock'n'roll sparks ideas as to how he picked up on the subject matter of his most recent book. As a result, his descriptions of performances by Arthur Brown and his analysis of Brian Jones' interest in Moroccan Joujouka music bring to mind famed occultist Aleister Crowley's own definition of magic [magick]: "the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will."

Despite Bebergal's academic background as an Harvard Divinity School graduate, Season of the Witch comes off as a travel companion for the reader interested in whatever falls under the author's elastic definition of the word "occult."

While the outline of some stories included in the book might be familiar to many of Bebergal's audience, Season of the Witch goes way beyond rock'n'roll by touching upon musique concrete, hip hop, classical composers, electronic, ambient, free jazz, West African tribal music, stoner rock and death metal. Although some critics have expressed mixed feelings about Bebergal's regular back and forth between figures and eras, the subject matter's latitude makes it hard not to do so.

Consequently, the author's investigation of the influence of well-known occult figures (Gurdjieff, Crowley, LaVey, Osman Spare, Blavatsky, Mahesh Yogi, etc.) on music suggests the idea that there is a meeting of minds. In Season of the Witch, the external world, as seen through "occult lenses," becomes an art in itself — be it Charles Manson's mind control, Jaz Coleman's lyrics, George Harrison's immersion into Western philosophy, H.R. Giger's artwork for Brain Salad Surgery or Genesis P-Orridge's performances with COUM.

However, Season of the Witch's strongest moments are, without a doubt, Bebergal's analysis of the origins of the blues and his debunking of Robert Johnson's alleged pact with the Devil. As part of his investigation, Bebergal delves into conspiracy theories, Dungeons & Dragons, Greek mythology, LaVayan Satanism and neo-paganism. Under his eyes, the whole world becomes kaleidoscope and collides against a certain triumph of order and sanity in the age of fragmentation.

Strangely enough, Bebergal's authoritative account of how the supernatural shaped modern music leaves black metal out of the picture. The last chapters, which mention stoner rockers such as Sleep and OM, as well as Swedish arsonists-cum-deathmetalists (the latter of whom were essentially influenced by their Norwegian black metal counterparts), could — in the opinion of this critic — have used some tales about the Helvete shop and members of the "black circle."

In the end, the book does raise the question proposed by its title: Did the occult really save rock'n'roll? Probably not, but it did cause change to occur in conformity with some of its protagonists' will.