"Welcome to NBC and the Elvis Presley special," producer Bob Finkel tells the audience at the network's studios in Burbank, CA. "Ladies and gentleman, Mr. Elvis Presley..."

As the audience cheers, all eyes are on the small red and white stage in the middle of the studio. Old bandmates Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana, plus a couple of musically inclined friends, Charlie Hodge and Alan Fortas, are seated, ready and poised. But the main event — the name on the special — is a ball of nerves backstage, delaying his return for just a few minutes longer.

The story goes that the director of the special, Steve Binder, high-tailed it over to the makeup room where Elvis stood, unable to take the stage. Elvis, the kid from Tupelo, MS, who changed the world with his rockabilly swagger, was literally drawing a blank. He couldn't remember his own songs, let alone the various talking points he and Binder had agreed upon. The singer whose gyrations caused an uproar across America was now at a standstill, frozen in place.

Binder says he told Elvis to get out there, even if just to say hello — at the very least, he had to step onto that stage. He then grabbed a piece of paper and wrote out the talking points as best as he could remember, and left Elvis alone in the room.

Moments later, the King of Rock 'n' Roll emerged from the shadows and reclaimed his throne.

We'll never know what was going through Elvis's head in those few minutes and what exactly made him decide to join his band on stage instead of running home to Beverly Hills, but one thing is for sure: in a short period of time, Elvis and Binder developed a trust that made the singer's return to music a resounding success.

What began as an ill-advised Christmas special, Singer Presents... Elvis — or, as it is better known today, The '68 Comeback Special — became the resuscitation of a legendary artist's career. At only 33 years of age, Elvis was already making his second return to music. The first was in 1960 following a two-year absence after being drafted into military service at the height of his popularity; but, unlike his years stowed away in an army base in Germany, the years leading up to The '68 Comeback Special weren't spent out of the public eye. Rather, his most recent need for a comeback was the result of a dwindling Hollywood career.

"I think he had lost his ability to be objective in terms of evaluating his own talent," Binder tells Exclaim! from his home office in California. "What really excited me about The '68 Special, which probably most people didn't notice, [was the] metamorphosis of a man who had lost faith in his own talent rediscover himself."

In a new documentary, Reinventing Elvis: The '68 Comeback Special (streaming now on Paramount+), Binder (who serves as an executive producer on the film) and a few of his associates who worked on the show with Elvis take us behind the scenes in the making of The '68 Comeback Special, as well as illustrating its significance. As the director of the show, Binder's perspective is immeasurable to the film, but his involvement wasn't necessarily a given.

"When my partner, Spencer Proffer, and [the] wonderful documentary filmmaker John Scheinfeld approached me, I said I didn't want to even get involved," Binder recalls. "They pitched me the idea that this was not going to be necessarily 100 percent about Elvis — it was gonna be a buddy story about [me] and Elvis. I was intrigued."

Fans and music historians have examined the many relationships of Elvis with a fine-tooth comb: the close bond between him and his mother, Gladys Presley; the sycophantic nature of his inner circle, the so-called Memphis Mafia; his friendship with Tom Jones and disdain for Robert Goulet; his marriage to ex-wife Priscilla; and his star-crossed love affair with screen icon Ann-Margret, to name but a few. But no two relationships have created the biggest "what if?" fork in the road in Elvis Presley lore than his friendship with Binder and his enduring professional relationship with manager Colonel Tom Parker.

"He [Parker] was nothing but a pain in the ass to me," Binder says sharply, citing the many road blocks Parker threw his way while developing and filming the special. "He had no clue about Elvis's talent. He was only interested in the dollar. He even told me when he first saw Elvis perform, I think it was at the Louisiana Hayride, he didn't pay attention to Elvis on stage at all. He was just looking at all these girls in the audience going crazy and he said, 'Whoever is making them react like that is somebody I want to get involved with.'"

In the years after Elvis's passing, the extent of Parker's unethical business practices has become apparent, and their dynamic has been painted in a Faustian light. Parker was known to exercise an uncomfortable degree of control over Elvis's life and career, ensuring that those closest to the singer were willing to fall in line with the manager's agenda. Binder was not that.

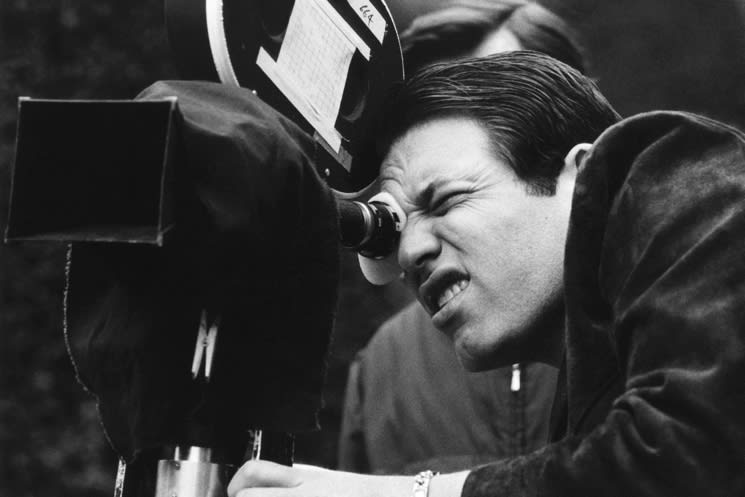

Prior to The '68 Comeback Special, the then-35-year-old had directed the innovative concert film T.A.M.I. Show that showed off the kinetic energy of James Brown, and a Petula Clark NBC special that raised eyebrows when Clark touched Harry Belafonte's arm, the first time a man and woman of different races made physical contact on American television. Binder was a filmmaker for a new generation, with ideas that went against the grain of the past — an independent thinker who had gained Elvis's trust and friendship, and who Parker saw as trouble.

"I'd spent so much time with Elvis and we had so many intimate moments. We were in my offices on the Sunset Strip when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel," remembers Binder. "We watched it live on a television set in my office and spent the rest of the evening talking about what's going on with our country with all these assassinations, the war, and the protests from the kids on campuses throughout the country. [We] just forgot about the television special."

Conversations about Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassinations lead to "If I Can Dream," the closing number of The '68 Comeback Special. The song didn't make big waves when it was released, and Parker is said to have shouted, "Over my dead body!" when he first heard the song. But it is a song that continues to resonate loudly today and is the gateway for many discovering Elvis's artistry, beliefs and philosophy.

Many Elvis fans have wondered what could have been had Binder taken the reigns from Parker. "Elvis had expressed to me personally, one on one, all the things he wanted to do after The '68 Special," Binder shares. "He wanted to travel the world and meet all of his fans. He said, 'I'll never record a record that I don't believe in again, I'll never make a movie that I don't love the script,' and so forth."

Binder continues, "I was persona non grata as far as having any communication with Elvis after [the special]. The Colonel made him a Las Vegas saloon singer, and it was tragic because I knew [Elvis] had so much to give the world in terms of his talent and himself."

Although Binder's name is forever entwined in one of the most pivotal periods of Elvis's history, their actual relationship only lasted a few months. In that short time, Elvis took chances reminiscent of his early years, unheard of since 1961's Blue Hawaii. He sang a protest song, he recorded with a full orchestra as opposed to the smaller rhythm section he was accustom to, and, on June 27, 1968, in spite of every doubt swimming through his head, Elvis stepped out from the makeup room, picked up his guitar and sang "Heartbreak Hotel" for the first time to an audience in nearly a decade.

The common thread in all these instances is the insistence of Steve Binder that Elvis simply try. If he didn't like "If I Can Dream," they'd scrap it. If he didn't like how he sounded with an orchestra, they'd keep the rhythm section and send the rest packing. If Elvis really didn't want to finish the improv segment (which was the first televised unplugged session), they'd pull him off the stage and dismiss the crowd. All Binder asked of Elvis was that he at least show up.

What was it that made Elvis trust Mr. Binder so earnestly? At this juncture in his career had Singer Presents... Elvis failed, Elvis Presley's career would have likely ended after his final movie contracts were fulfilled the following year. So why did Elvis, who had everything to lose, place all of his faith in a relative stranger?

We'll never know of course, but I get a better idea when I ask Mr. Binder what he took away from the special that changed his career.

"I have never put one project ahead of another. I've always treated every special, every project, every film I've done, as the most important thing in my life," he responds. "I never put anybody on a pedestal."

For as extraordinary his life and talent, Elvis was — and is — known for his disarming humility, never treating anyone less than or greater than. Perhaps, in this regard, he saw Binder as a like-minded soul amidst a sea of disingenuous show business types.

Whatever the reason, because Elvis placed his trust in the right person at the right time, he was given a much-deserved second chance to prove his place in music history — and he did 10 times over.

As for Binder, he had an exceptionally successful career in television and film for 30 years after working with Elvis. Even if he doesn't put The '68 Comeback Special above anything else he's ever done, he's aware of the association and will forever treasure the experience: "Somebody said, years and years ago, 'Steve, no matter what projects you ever do, you're going to always be remembered as the guy who worked with Elvis Presley and brought his career back.'

"Thank God I had the opportunity to work with him. It is definitely something that I will cherish — those are memories for an entire lifetime."

As the audience cheers, all eyes are on the small red and white stage in the middle of the studio. Old bandmates Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana, plus a couple of musically inclined friends, Charlie Hodge and Alan Fortas, are seated, ready and poised. But the main event — the name on the special — is a ball of nerves backstage, delaying his return for just a few minutes longer.

The story goes that the director of the special, Steve Binder, high-tailed it over to the makeup room where Elvis stood, unable to take the stage. Elvis, the kid from Tupelo, MS, who changed the world with his rockabilly swagger, was literally drawing a blank. He couldn't remember his own songs, let alone the various talking points he and Binder had agreed upon. The singer whose gyrations caused an uproar across America was now at a standstill, frozen in place.

Binder says he told Elvis to get out there, even if just to say hello — at the very least, he had to step onto that stage. He then grabbed a piece of paper and wrote out the talking points as best as he could remember, and left Elvis alone in the room.

Moments later, the King of Rock 'n' Roll emerged from the shadows and reclaimed his throne.

We'll never know what was going through Elvis's head in those few minutes and what exactly made him decide to join his band on stage instead of running home to Beverly Hills, but one thing is for sure: in a short period of time, Elvis and Binder developed a trust that made the singer's return to music a resounding success.

What began as an ill-advised Christmas special, Singer Presents... Elvis — or, as it is better known today, The '68 Comeback Special — became the resuscitation of a legendary artist's career. At only 33 years of age, Elvis was already making his second return to music. The first was in 1960 following a two-year absence after being drafted into military service at the height of his popularity; but, unlike his years stowed away in an army base in Germany, the years leading up to The '68 Comeback Special weren't spent out of the public eye. Rather, his most recent need for a comeback was the result of a dwindling Hollywood career.

"I think he had lost his ability to be objective in terms of evaluating his own talent," Binder tells Exclaim! from his home office in California. "What really excited me about The '68 Special, which probably most people didn't notice, [was the] metamorphosis of a man who had lost faith in his own talent rediscover himself."

In a new documentary, Reinventing Elvis: The '68 Comeback Special (streaming now on Paramount+), Binder (who serves as an executive producer on the film) and a few of his associates who worked on the show with Elvis take us behind the scenes in the making of The '68 Comeback Special, as well as illustrating its significance. As the director of the show, Binder's perspective is immeasurable to the film, but his involvement wasn't necessarily a given.

"When my partner, Spencer Proffer, and [the] wonderful documentary filmmaker John Scheinfeld approached me, I said I didn't want to even get involved," Binder recalls. "They pitched me the idea that this was not going to be necessarily 100 percent about Elvis — it was gonna be a buddy story about [me] and Elvis. I was intrigued."

Fans and music historians have examined the many relationships of Elvis with a fine-tooth comb: the close bond between him and his mother, Gladys Presley; the sycophantic nature of his inner circle, the so-called Memphis Mafia; his friendship with Tom Jones and disdain for Robert Goulet; his marriage to ex-wife Priscilla; and his star-crossed love affair with screen icon Ann-Margret, to name but a few. But no two relationships have created the biggest "what if?" fork in the road in Elvis Presley lore than his friendship with Binder and his enduring professional relationship with manager Colonel Tom Parker.

"He [Parker] was nothing but a pain in the ass to me," Binder says sharply, citing the many road blocks Parker threw his way while developing and filming the special. "He had no clue about Elvis's talent. He was only interested in the dollar. He even told me when he first saw Elvis perform, I think it was at the Louisiana Hayride, he didn't pay attention to Elvis on stage at all. He was just looking at all these girls in the audience going crazy and he said, 'Whoever is making them react like that is somebody I want to get involved with.'"

In the years after Elvis's passing, the extent of Parker's unethical business practices has become apparent, and their dynamic has been painted in a Faustian light. Parker was known to exercise an uncomfortable degree of control over Elvis's life and career, ensuring that those closest to the singer were willing to fall in line with the manager's agenda. Binder was not that.

Prior to The '68 Comeback Special, the then-35-year-old had directed the innovative concert film T.A.M.I. Show that showed off the kinetic energy of James Brown, and a Petula Clark NBC special that raised eyebrows when Clark touched Harry Belafonte's arm, the first time a man and woman of different races made physical contact on American television. Binder was a filmmaker for a new generation, with ideas that went against the grain of the past — an independent thinker who had gained Elvis's trust and friendship, and who Parker saw as trouble.

"I'd spent so much time with Elvis and we had so many intimate moments. We were in my offices on the Sunset Strip when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel," remembers Binder. "We watched it live on a television set in my office and spent the rest of the evening talking about what's going on with our country with all these assassinations, the war, and the protests from the kids on campuses throughout the country. [We] just forgot about the television special."

Conversations about Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassinations lead to "If I Can Dream," the closing number of The '68 Comeback Special. The song didn't make big waves when it was released, and Parker is said to have shouted, "Over my dead body!" when he first heard the song. But it is a song that continues to resonate loudly today and is the gateway for many discovering Elvis's artistry, beliefs and philosophy.

Many Elvis fans have wondered what could have been had Binder taken the reigns from Parker. "Elvis had expressed to me personally, one on one, all the things he wanted to do after The '68 Special," Binder shares. "He wanted to travel the world and meet all of his fans. He said, 'I'll never record a record that I don't believe in again, I'll never make a movie that I don't love the script,' and so forth."

Binder continues, "I was persona non grata as far as having any communication with Elvis after [the special]. The Colonel made him a Las Vegas saloon singer, and it was tragic because I knew [Elvis] had so much to give the world in terms of his talent and himself."

Although Binder's name is forever entwined in one of the most pivotal periods of Elvis's history, their actual relationship only lasted a few months. In that short time, Elvis took chances reminiscent of his early years, unheard of since 1961's Blue Hawaii. He sang a protest song, he recorded with a full orchestra as opposed to the smaller rhythm section he was accustom to, and, on June 27, 1968, in spite of every doubt swimming through his head, Elvis stepped out from the makeup room, picked up his guitar and sang "Heartbreak Hotel" for the first time to an audience in nearly a decade.

The common thread in all these instances is the insistence of Steve Binder that Elvis simply try. If he didn't like "If I Can Dream," they'd scrap it. If he didn't like how he sounded with an orchestra, they'd keep the rhythm section and send the rest packing. If Elvis really didn't want to finish the improv segment (which was the first televised unplugged session), they'd pull him off the stage and dismiss the crowd. All Binder asked of Elvis was that he at least show up.

What was it that made Elvis trust Mr. Binder so earnestly? At this juncture in his career had Singer Presents... Elvis failed, Elvis Presley's career would have likely ended after his final movie contracts were fulfilled the following year. So why did Elvis, who had everything to lose, place all of his faith in a relative stranger?

We'll never know of course, but I get a better idea when I ask Mr. Binder what he took away from the special that changed his career.

"I have never put one project ahead of another. I've always treated every special, every project, every film I've done, as the most important thing in my life," he responds. "I never put anybody on a pedestal."

For as extraordinary his life and talent, Elvis was — and is — known for his disarming humility, never treating anyone less than or greater than. Perhaps, in this regard, he saw Binder as a like-minded soul amidst a sea of disingenuous show business types.

Whatever the reason, because Elvis placed his trust in the right person at the right time, he was given a much-deserved second chance to prove his place in music history — and he did 10 times over.

As for Binder, he had an exceptionally successful career in television and film for 30 years after working with Elvis. Even if he doesn't put The '68 Comeback Special above anything else he's ever done, he's aware of the association and will forever treasure the experience: "Somebody said, years and years ago, 'Steve, no matter what projects you ever do, you're going to always be remembered as the guy who worked with Elvis Presley and brought his career back.'

"Thank God I had the opportunity to work with him. It is definitely something that I will cherish — those are memories for an entire lifetime."